The changing funding landscape

The changing funding landscape

Professor Danie Visser

Deputy Vice-Chancellor

We need to think hard about how to meet these challenges – how to garner the resources necessary to sustain and advance our global position as a university.

A glance through this report demonstrates the extraordinary research that takes place within the walls of the University of Cape Town. Our researchers are expanding knowledge in all directions, offering insight into global problems and innovation in strategies to solve them; contributing to public policy, the arts, our communities and the natural world. In many areas of research, we lead the world and attract some of the very best local and international researchers.

Such research, however, comes at a price, and it is an increasing headache for units to fund it within already tightened university budgets and competing priorites.

Government funding continues to be an important component in our research resources, mainly through the Department of Science and Technology (DST), the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) and the National Research Foundation (NRF). However, this source of funding has not kept up with demand, as both the numbers (of students and researchers) and the cost of cutting-edge research have grown. Per-capita funding of researchers has declined significantly in real terms in the last 10 years, and this is unlikely to change in the current and predicted economic landscape.

As a result, the University of Cape Town has had to turn increasingly to external sources of funding, and we expect that the need for external funds will only rise in the coming years. We have already had considerable success here: for instance, our research income in 2013 was just under R1 billion, and the value of new research contracts signed in 2013 raised almost a further R1 billion. Our ability to attract funding from foreign governments and donors is already a major factor in our survival as a top-ranked university, and we punch way above our weight.

This gives us real optimism for the future. However, significant challenges remain. Not only is the amount of funding we receive from the state dwindling, but also our competitors have access to a level of funding that we can only dream about – and not just in the developed world. For instance, the recent revelation that the University of Cape Town has been ranked in the top 10 universities within the BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) in the 2014 QS University Rankings and third in the latest Times Higher Education Ranking of Universities in the Developing World is pleasing, but also shows the competition we are up against. China has increased its research and development funding by an average of 18% a year since 2008, and it has 71 universities in the top 200. India has none in the top 10 but intends to set up 14 world-class universities under the government’s “brain gain” policy.

We need to think hard about how to meet these challenges – how to garner the resources necessary to sustain and advance our global position as a university.

Interdisciplinarity

To some degree, this simply requires an escalation of what we are already doing. A key pillar in our research strategy is interdisciplinarity. Over the past 20 years, there has been increasing recognition of the importance of research for the generation of new knowledge at the interfaces of disciplines in order to address complex societal issues, such as climate change, health and urban planning. The most rapidly expanding areas of published research are in interdisciplinary clusters, and international funders increasingly focus their funding on interdisciplinary research projects.

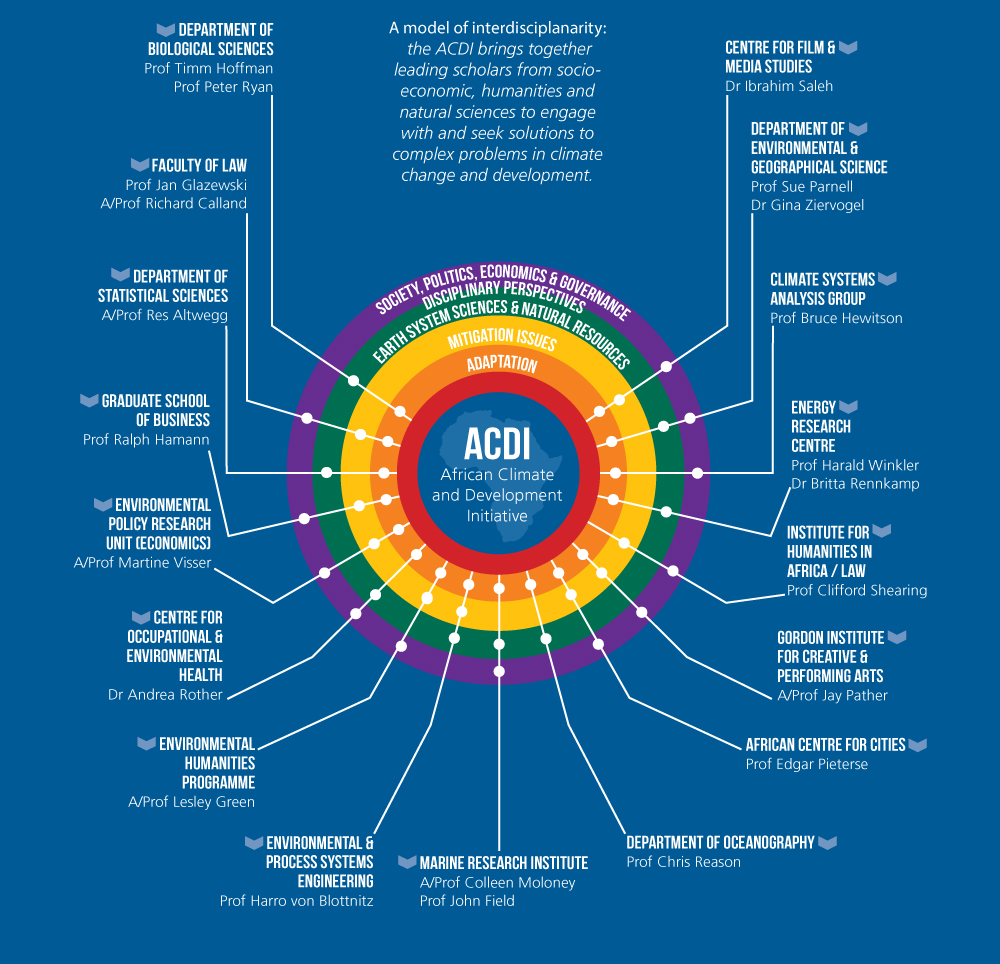

It is therefore not surprising that many leading international universities have invested in interdisciplinary research. The University of Cape Town has responded to this for years with a number of strategies. The Six Signature Themes (see p38) were formed to foster research that would stimulate cross-faculty collaboration and challenge the “business as usual” approach to research. Similarly, the institution-wide strategic initiatives led by the Vice-Chancellor were instituted with the explicit mandate of undertaking interdisciplinary research and the graphic of the African Climate and Development Initiative (see right), illustrates how successful this has been.

Transdisciplinary research takes this even further with opportunities for engagement with the community in our city, region and continent, bringing in perspectives from outside the academy and ensuring that our research is relevant and has the maximum possible impact where it matters most.

However, the significant institutional barriers to interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research, such as faculty and departmental structures and budgets, continue to work against us and remind us that we must intensify our efforts. The university has set up a task team to analyse both barriers and enablers to interdisciplinary research and to come up with suggested strategies to encourage and enhance it. It will require significant levels of funding and institutional changes; however, we should be repaid with innovative research that addresses societal problems more effectively and that will, in turn, attract more international funding.

Internationalisation

We also need an enhanced approach to the internationalisation of our research, with a simultaneous emphasis on global partnerships for postgraduate training and collaborative research.One of the great challenges and a key focus for the university is growing the next generation of researchers. Our move towards a research-intensive university requires an increase in postgraduates, which in turn requires an increase in supervisory capacity. This works against the national trend in which the government gives more money to undergraduates and the amount we receive for each postgraduate student declines in real terms.

As the leading research university in Africa, the University of Cape Town already provides a portal into Africa

for universities abroad.

We therefore cannot approach this challenge with ad hoc responses to opportunities that come our way. Instead, we must put in place concrete strategies that will leverage funding and increase capacity.

One such strategy that began to take shape in 2013/14 is to position the University of Cape Town as a preferred partner with the Global North and the Global South. As the leading research university in Africa, the University of Cape Town already provides a portal into Africa for universities abroad. This is partly because we have strong management and administrative practices; it is also because we act as a principal site of engagement on issues that are unique to our continent but have global impact. Examples include areas where our geographical advantage or socio-economic realities provide live laboratories for research on sustainable environments, linguistics and patterns of disease, among many others.

This has led to a rich tapestry of collaborations that we intend to augment with three-way global partnerships for PhD training and supervision: between the University of Cape Town, the Global North and the Global South (particularly the rest of Africa). We propose to put in place mobility funds and PhD packages, and will focus our initial efforts where there are existing and productive research collaborations. This should increase the number of PhD students we can supervise, supplement current PhD training practice, and produce exceptionally well-trained researchers whose work is globally competitive.

Changing the world

We are unashamedly ambitious for our researchers and the work they produce. Research can and does transform the world and the University of Cape Town is determined to be among those leading the charge. To produce this innovative research, we have to be innovative in the ways we fund it. Against this backdrop of increasing financial pressure, I am especially grateful to our donors and sponsors who contribute so generously to research at UCT, without whom we would be unable to realise our ambitions in the global research arena.

Funding Facts

- Almost 45% of our research contract funding came from foreign non-profit organisations in 2013.

- The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation was the most significant contributor to this, funding research contracts worth more than R170 million in 2013, an enormous leap up from just over R40 million the year before.

- The University of Cape Town attracted more than US$9 million in direct grants from the National Institutes of Health in the USA in 2013: more than any other university outside America.

- Professor Kelly Chibale has attracted grants worth more than R200 million since 1997; in 2013 alone, he attracted R53 million. Around half of this funding is for the important work he does as founder and director of the Drug Discovery and Development Centre.

- The amount raised by the Faculty of Science from non-governmental sources increased by 50% in 2013 from the previous year to almost R70 million.

- The African Climate and Development Initiative is leading a project on Adaptation at Scale in Semi-arid Regions funded by Canada’s International Development Research Centre and the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development to the tune of CAD $13,5 over five years.

- The TY Danjuma Fund for Law and Policy Development in Africa endowed the Centre for Comparative Law in Africa with US $5 million to support research, capacity building and research dissemination.

- The United Kingdom’s Wellcome Trust entered into research contracts to the value of just below R87 million (compared to R24.5 million the previous year), while research contracts with the Economic and Social Research Centre were worth almost R5 million.