Preserving Africa’s past to build a continent’s future

As the trend of globalisation continues, scholars the world over are raising all-important questions of identity, independence and power dynamics. Within this movement, the African continent is reconstructing its identity and position in the world, and it is important that this process takes place within a discourse of empowerment and cohesion.

Global economic forces continue to have an impact on the African continent, which causes some scholars to raise concerns that this is a threat to African identity, referring to globalisation as a form of neo-colonialism that forces Africans to become nameless actors on the world stage. Other scholars are more optimistic, moving beyond Afro-pessimism to position Africa on the world stage as a unique power, finally harnessing its resources for its own empowerment. Either way, one thing is clear: during this time of rapid development, it is essential that Africans are empowered to shape their own identity and tell their own stories.

The idea that narrative shapes identity is not new. Without narrative, it is difficult to understand human temporality and historicity at all. It is therefore critical that, in the formation of narratives across the African continent, the heritage of its people is, first, preserved and not destroyed, and second, preserved in its own context, rather than reframed through a Western gaze.

For South Africa, there is also a further need for narrative, and that is its healing function. As the country’s democracy matures and it recovers from its splintered past, narrative can play a powerful part in the healing of trauma. Giving voice to the various histories of the country and continent is therefore a critical part of this process of respect, growth and healing. It is to this end that UCT researchers have dedicated their time and resources to preserving African heritage, specifically preserving it as closely and respectfully as possible to its original context.

Embracing the political

In 2013, an attack on the Ahmed Baba Centre library in Timbuktu, Mali, highlighted the politically charged nature of preserving – or destroying – heritage pieces. Dr Shamil Jeppie, team leader of the Timbouctou Manuscripts Project, described the attack as “crude” and pointed out the need to develop “consciousness and awareness” of how to care for this kind of ancient artefact on the African continent.

The documents destroyed at the time included Qur’ans that possibly dated back as far as the 14th century, and other valuable manuscripts that were being digitised at the time by UCT scholars to form a multi-volume catalogue. “The rebels were very destructive of a tradition of learning that goes back centuries,”

Dr Jeppie said, pointing out the need for these texts to be kept in a “living environment” to protect them from neglect which, he added, could be nearly as destructive as actively destroying them. Highlighted in this example is the idea that the preservation of these manuscripts is necessarily a political act – one continuing UCT’s tradition of activism and the importance of the work done by UCT and other scholars in protecting the manuscripts. As pointed out by Jeppie at the time, the research was not nearly as badly affected as it might have been, given that the new library archive had already been completed in 2009 and the move was in progress at the time of the attack. And apart from this good timing, scholars rallied together to protect the learning that was at stake.

As has long been the case in Timbuktu, researchers and librarians ultimately become the custodians of knowledge at times of political threat. According to the Global Post’s report on these unlikely heroes of the rebel invasion: “Each time foreign invaders threaten Timbuktu – whether a Moroccan army in the 16th century, European explorers in the 18th, French colonialists in the 19th or Al Qaeda militants in the 21st – the manuscripts disappear beneath mud floors, into cupboards, boxes, sacks and secret rooms, into caves in the desert or upriver to the safety of Mopti or Bamako, Mali’s capital.”

Dr Jeppie explained: “The custodians of the libraries worked quietly throughout the rebel occupation of Timbuktu to ensure the safety of their materials. A limited number of items [were] damaged or stolen, the infrastructure neglected and furnishings in the Ahmad Baba Institute library looted but … there was no malicious destruction.”

Dr Jeppie is the Director of the Institute of Humanities in Africa (HUMA), and brought the Timbouctou Manuscripts Project to that institute from the Department of History, where it had flourished for many years.

Timbuktu was a great centre of learning and was famous in West Africa and far beyond, from the 13th to the 20th centuries. Local scholars and their students recorded their scholarship in a number of diverse areas in handwritten texts. Unesco declared Timbuktu a World Heritage Site in 1990. A selection of legal texts (initially 100 manuscripts of varying size) was digitised at the Mamma Haidara Library in Timbuktu in January 2004. Another 60 manuscripts from the Ahmed Baba collection were subsequently also digitised for research by the project. Some of these digitised texts have since been translated into English and studied further, serving as a basis for research, including doctoral and master’s thesis work. The scope of the project continues to broaden to include writing cultures from other parts of Africa, namely collections from Mozambique and Madagascar (in Arabic and Malagasy), as well as Zanzibar (Arabic and Swahili) and Somalia. There is also a great deal of Coptic Christian writing from Ethiopia in Amharic, and there are texts written in Arabic and Amharic in archives in Addis Ababa.

HUMA, meanwhile, continues to foster critical research and seeks to bring the fruits of that research into the public arena for debate, to make it accessible to the public. The humanities are vital to the creative and critical energies of societies in the throes of profound change. HUMA fosters interdisciplinary study through the humanities as a whole, stimulating debate and fostering growth in the broader community outside UCT.

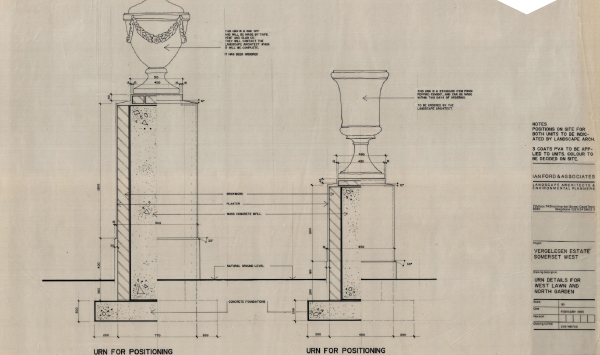

Diagram detail of an urn in the north garden of Vergelegen Estate from the Ian Ford Archive in the School of Architecture. After graduating with a B Arch from UCT, Ian Ford studied landscape architecture at Edinburgh University. His design work includes several highly significant South African heritage sites including Groot Constantia, Steenberg and Vergelegen.

The struggle against forgetting

Milan Kundera writes in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, “The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.”

He adds, “The future is only an indifferent void that nobody cares about, but the past is filled with life, and its countenance is irritating, repellent, wounding, to the point that we destroy or repaint it. We want to be the masters of the future only for the power to change the past. We fight for access to the labs where we can retouch photos and rewrite biographies and history.”

When it comes to the histories of traditionally marginalised people, the process that UCT is busy with is therefore one of empowerment, and it is a critical one – especially in the case of people whose languages and cultures are dying out or whose stories have never been told. Here, the preservation of the memory of the past in the voices of the people themselves – and ensuring that the narratives are not overwritten by the scholars and academics, and are instead preserved respectfully and intact – becomes vital.

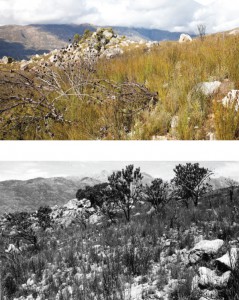

Repeat photograph of landscapes (Botany Department, Plant Conservation Unit), an emerging discipline within the global change research community to document the extent and rate of change in the vegetation of southern Africa. The images are now part of the growing UCT digital archive.

One such project is ongoing at the Centre for Curating the Archive (CCA). It began life as LLAREC (the Lucy Lloyd Archive, Resource and Exhibition Centre) in the late 1990s as a space in which material – original and reproduced, created and found – was collected from a variety of archives, museums, collections, storerooms, offices and junk heaps and used creatively in exhibitions curated by artist-staff at the Michaelis School of Fine Art. It is now an interdisciplinary space with links to various UCT departments and projects, such as Professor Carolyn Hamilton’s Archive and Public Culture initiative. The CCA is also concerned with the expanded archive relating to the study and representation of the San, particularly the |xam, from the early 19th century. This focus has sought to expose the rich intellectual lives of the San, most often represented as a people without history and as a part of “nature”, by reaching into the pre-colonial archive through the Bleek and Lloyd collection of |xam and !kun texts, as well as other sources of storytelling, and through an examination of rock art. In the past, several significant publications have emerged from this focus, not least the publication of the 14 000 pages of 19th-century interviews with |xam prisoners in Claim to the Country (Skotnes, 2007) and the George Stow collection in Unconquerable Spirit (Skotnes, 2008).

Significant ongoing research projects include extensive studies relating to archaeological material, as well as the continuing digitisation and study of documents relating to the expanded Bleek and Lloyd archive, and the |xam dictionary, plus documents relating to the Special Mission of Louis Anthing. Anthing, in the 1860s, recorded interviews with San (|xam) survivors of massacres perpetrated by farmers on the colonial borders of the Cape Colony, and is therefore a vital source of this marginalised historical narrative.

The challenge of curatorship and archiving remains to empower the storytellers to narrate, as far as possible, their own histories and contexts.

A further important project includes fieldwork and interviews with descendants in the Northern Cape who, though the |xam language is extinct, still retain a lively and previously unrecorded oral tradition that bears many similarities to stories told in the 1860s and 1870s.

“There is a huge archival repository that resides, so to speak, in the landscape and communities of the Northern Cape, where the death of the language of the |xam was thought to have resulted in the death of oral traditions,” says Pippa Skotnes, professor of fine art and director of the Centre for Curating the Archive. “Not only do these appear to be alive – while not in |xam, but in Afrikaans – but there are also significant sites in the landscape where people lived and died that could well be identified and exposed along with their associated histories. A postdoctoral fellow at the CCA began work in this area, and we hope soon to identify a new postdoc to continue this work.”

In terms of constructing a narrative, the challenge of curatorship and archiving remains to empower the storytellers to narrate, as far as possible, their own histories and contexts. Professor Skotnes explains, “There is a huge repository of archival material in the form of documents, photographs and object collections in our museums, library and archives, but also in university collections – loosely gathered in departments, offices and laboratories.”

An image of the Alfred Basin, Cape Town harbour, from the Cape Argus image archive, an extensive archive of about 850,000 images, now housed at UCT, which spans a period from about 1940 to 2000. The archive is housed and managed by UCT Special Collections.

Much of this material can be stored digitally, and the Humanitec initiative, a successful partnership between the Faculty of Humanities and UCT Libraries that is funded by the Vice-Chancellor’s strategic fund for five years (2011 to 2015), is bringing into being an institution-wide digital repository for this purpose. Working in collaboration with Information and Communication Technology Services (ICTS), the initiative is intended to unify the multiplicity of digital activity around the university by providing a scaleable location where material can be stored and managed.

“Such material has the potential to say much about our mutual and separate histories, but it needs recognition, conservation and publication in two forms: one the normal scholarly publication, but also curatorship – the process by which objects and documents are brought together, to shed light on associated events and practices. The objects themselves are of interest, as are the evidentiary traces of the past.”

The CCA has recently received a substantial grant from the Mellon Foundation, which will be used to develop a programme in curatorship in partnership with Iziko Museums, and is intended to encourage students to think of new ways to expose archival heritage. “There is much to be done in the areas of conservation, but also the reimagining of how we expose the things that survive from our past,” says Professor Skotnes.

research on African languages has been dominated by foreign missionary linguists and non-African scholars who described and standardised AFRICAN languages.

Celebrating diversity

The work of the Centre for African Language Diversity (CALDi) is closely related to the work of the CCA. Its director, Dr Matthias Brenzinger, drives a custom-decorated car marked like an emergency vehicle designed to save languages in danger of dying. It’s an appropriate message, as thousands of languages are endangered and more than 100 African languages are on the verge of extinction.

Launched in November 2012, CALDi encourages and supports primary research into African languages. Its main aim is to foster the study and documentation of African languages and therefore to promote and actively support sustainable linguistic diversity on the African continent.

In addition to heading up CALDi, Dr Brenzinger also holds the AW Mellon Research Chair in African Language Diversity, is head of linguistics in AXL, and curator of the African Language Archive (TALA). He is passionate about the positive role language plays in the preservation of heritage and the understanding of history.

The study of African languages is an academic discipline that was developed and established in Europe. Dr Brenzinger says that, until today, research on African languages has been dominated by foreign missionary linguists and non-African scholars who came to the continent and analysed, described and standardised its languages. “CALDi’s mission is to transform the study of African languages into African linguistics, ie the study of African languages by African scholars on the African continent. For that reason, the training of African linguists is of utmost importance,” he says.

CALDi trains graduate students and young scholars from various parts of the African continent. This capacity building is urgently needed, especially in South Africa. According to Dr Brenzinger, “The language policy of the new South Africa is among the best in the world with regard to the recognition of language diversity,” he says. The country has 11 official languages, a unique and truly democratic choice by the post-apartheid government when you consider that in Africa 100 languages are spoken by just over one million people. “But the implementation of this language policy is not really happening, because of the lack of local expertise. That’s why it is so important to have African linguists trained on the continent,” says Dr Brenzinger.

CALDi members are from a wide range of countries: England, Germany, Malawi, Cameroon, Botswana, Ghana and Kenya, and the group hopes to inspire students in linguistics courses at UCT to study African linguistics. There is still the idea that English is a “better” language, and often little respect for and appreciation of African languages is given, even among native speakers, says Dr Brenzinger.

It’s an appropriate message, as thousands of languages are endangered and more than 100 African languages are on the verge of extinction.

However, despite the urgency, he believes that linguists can’t save languages. “The individual speakers decide which languages they teach to their children. And since peers are crucial for language acquisition, language communities, or at least networks of speakers, need to be maintained in order to allow languages to remain a vital medium of communication. Linguists, however, do have important roles to play in community language maintenance efforts, ie in developing practical orthographies for oral languages, in supporting the production of teaching and learning materials, and in documenting and archiving language data,” he says.

To this end, CALDi is working on numerous projects focusing on language documentation. In November 2013, it hosted an international conference, celebrating the pioneer linguist Ernst Westphal, professor of African languages at UCT from 1962 to 1984. A Humanitec grant enabled the digitising and archiving of Westphal’s audio tapes. Between the 1960s and 1980s, he recorded speakers of African languages, several of which are no longer spoken today, such as ||Xegwi and Kwadi, both non-Bantu click languages that were spoken in South Africa and Southern Angola respectively. Other languages captured are still spoken, such as Ts’ixa, with roughly 170 speakers in Mababe, a small village in the east of the Okavango Delta in Botswana. In 1964, Westphal interviewed the chief of Mababe, and returning this material to these speakers was highly appreciated – especially by his children. Preserving and returning such archived material is one of the objectives of CALDi. There are corresponding texts, too, which make the entire collection an invaluable resource for scholars of linguistics.

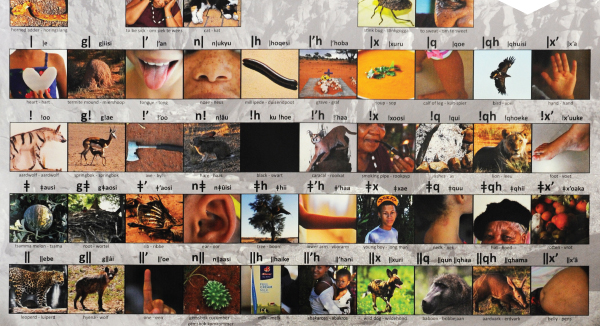

A further educational project, managed by CALDi postdoctoral fellow Dr Sheena Shah, is that of the last N||ng speakers – the CALDi N||ng Language Project. N||ng – with its N|uu and ||’Au varieties – is the last closely related language to |Xam. |Xam features prominently in the motto of the coat of arms of post-apartheid South Africa, but became extinct about 100 years ago. N||ng is spoken by only five remaining elderly speakers. ||’Au, an eastern variety of N||ng, is spoken by Hannie Koerant and Fytjie Sanna Rooi in Olifantshoek. The western N||ng variety, N|uu, is better known and is spoken by three sisters named Hanna Koper, Griet Seekoei and Katrina Esau. None of them use N||ng on a daily basis any more, communicating rather in Afrikaans, which is their mother tongue.

Katrina Esau, better known as Ouma Geelmeid, has been the most proactive of the remaining speakers in preserving the language. For the past nine years, she and her granddaughter, Claudia du Plessis, have been teaching N|uu to more than 30 children in the community. On 27 April 2014, she received the Order of the Baobab in Silver for these language maintenance efforts.

Since 2012, members of CALDi have supported these community teaching efforts. Together with the speakers, they developed a practical N||ng orthography, which was launched at a community workshop in March 2014. Illustrated alphabet charts and other N||ng language posters with translations in English, Afrikaans and ‡Khomani Nama are now being used in the community’s language maintenance activities.

Such efforts are vital, says Dr Brenzinger, because oral traditions conveyed and preserved in African languages are often the only key to understanding the past. “Languages spoken today allow for reconstructing migrations and other historical events. If we lose these languages, we lose an important source for understanding our history.”

Given that one-third of the world’s languages are spoken in Africa, language on the continent is of outstanding importance, especially as there are so few written records. “Language diversity is not a threat – it is a resource.”

Ouma Geelmeid, one of the last five speakers of N||ng, with her great grandchild Cleyve and granddaughter Claudia in Dr Matthias Brenzinger’s custom-decorated car marked like an emergency vehicle designed to save languages.

interrogating the archive

As Professor Njabulo S Ndebele, former Vice-Chancellor of UCT and Andrew W Mellon Research Fellow with the Archive and Public Culture (APC), puts it, “There can be no transformation of the curriculum, or indeed of knowledge itself, without an interrogation of archive.”

The Archive and Public Culture Research Initiative at UCT was established to grapple with critical questions about history, memory, identity and the public sphere in South Africa. Funded by the National Research Foundation (NRF) and based in AXL, this five-year interdisciplinary research project brings together leading established and emerging scholars and researchers to explore the workings of the archive in contemporary culture. American historian, Joyce Appleby points out: “Scientists think that the disciplined practices of the laboratory – seeing through the microscope and telescope – bring them closer to reality, but they are simply privileging the discourse that they speak, the technologies of their own self-fashioning … no reality can possibly transcend the discourse in which it is expressed.” It stands to reason, then, that an interdisciplinary approach is one with the greatest respect for knowledge or, at least, the greatest potential for exchange.

As part of this initiative, researchers engage with theoretical notions of archive and public culture, while also paying attention to the record. The project unites scholars from various disciplines – medicine, science, law and others – enhancing debate and transdisciplinary discourse. Emerging researchers and students are exposed to established scholars and vice versa, for maximum exposure to new ideas. There is intensive postgraduate engagement, mentoring and support.

The research initiative promotes a number of pedagogical innovations designed to build research capacity and to foster critical, independent enquiry. These include schooling students in relevant theory by encouraging a breadth of familiarity and depth of systematic engagement through careful reading of selected works, developing analytical skills, honing methodologies and driving processes of writing up and publishing research. Current projects undertaken by the initiative include regular research labs, which take place weekly and are open to all APC associates and guests, as appropriate. Says Professor Carolyn Hamilton, who holds the DST/NRF SARChI Chair in Archive and Public Culture: “The research labs offer a slot for a single piece of work in progress to receive … research development attention. Among other things, we are keen to use this as a supervision modelling occasion.”

There can be no transformation of the curriculum, or indeed of knowledge itself, without an interrogation of archive.

The initiative also hosts special events focused on work that is relevant to its field of enquiry, as well as bi-annual workshops that serve as a point of intellectual exchange between associates. “At each workshop, participants present their current work and engage in constructive debate. The workshops allow participants to become familiar with each other’s work as it develops over time and facilitate the production of papers and books for publication,” says Professor Hamilton.

Late in 2014, there will be the publication of the sixth volume of the James Stuart Archive, bringing to completion the first, and largest, phase of this publication project. During this time, the APC will also celebrate the scholarly achievements of one of its most senior associates, Professor John Britten Wright, in whose honour a conference will be held in 2015 and whose research base continues to be the Rock Art Research Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand, as he works on long-standing research projects in the pre-colonial history of the KwaZulu-Natal region.

Telling our own story

UCT remains a world-class destination for scholars and students alike, as it continues its proud tradition of carving out its history on the African continent – both as an academic institution and for the communities it serves. As South Africa continues to strive towards building its identity in a post-apartheid era, becoming empowered to tell its own story and take its place on the African continent, the scholars and students of UCT continue to work towards slowly, carefully, respectfully preserving each surviving part of that narrative.